Divided Legacy

Freiburg, Oct 30, 2019

Popular representations of historical events lend themselves well to researching the culture of remembrance because they have a decisive influence on people’s historical awareness. Whether it’s movies like “Good Bye, Lenin!,” TV series such as “Weißensee,” novels like “89/90,” or graphic novels such as “Kinderland,” researchers from the Universities of Freiburg and Leipzig are studying different ways of interpreting and reinterpreting what is probably the most important event in recent inner German history.

Stories of the revolution: Researchers are exploring the different interpretations of the fall of the wall. Photo: snapshot-photography/SZ Photo/Timeline Images

With flickering candles in their hands, citizens of East Germany set out from the St. Nicholas Church in Leipzig on the evening of October 9, 1989. The army and paramilitary combat groups stood by, while tens of thousands of people marched past the State Security Service (Stasi) building and the Town Hall. They kept chanting: “We are the people!” The march remained peaceful, and four weeks later, the wall fell. In this year of the 30th anniversary of what could be considered the most significant event in recent inner German history, these scenes have again become omnipresent in newspapers, films, and TV programs. “These images convey emotions and point to the coming breakdown of the political system and to the reunification,” explains the historian Dr. Anna Lux from the University of Freiburg.

However, the widespread interpretation of events from ’89 as an inevitable story of success only partially corresponds with the historical facts. The events were actually much more multifaceted and sometimes more contradictory than they were portrayed in public and in many popular media formats. As part of the collaborative project “Das umstrittene Erbe von 1989” (The Contested Legacy of 1989), Lux investigates the different interpretations and reinterpretations of this time. The collaboration involves researchers from sociology and history from the Universities of Freiburg and Leipzig and is funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research.

Multifaceted and contradictory

Disagreements regarding the remembrance of 1989 have defined public debates in Germany since the 1990s. According to the historian Prof. Dr. Martin Sabrow from Potsdam, the politics of history is dominated by so-called “revolutionary memory,” which “is represented by influential actors of the civil rights movement at the time,” says Lux. “According to this, the opposition’s protests against the regime of injustice made an essential contribution to the growing protest movement and the Monday demonstrations, ultimately culminating in the reunification.”

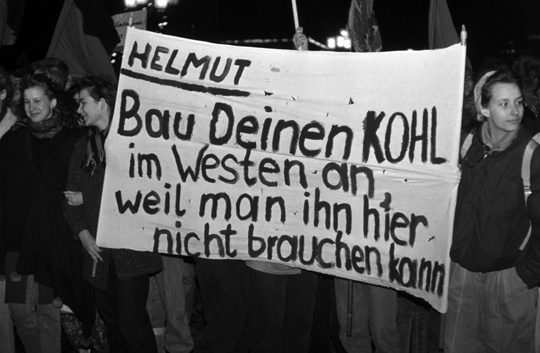

This narrative of revolution defines the culture of remembrance not only in the media, but also in schools, says Lux. Meanwhile, other types of experiences have been marginalized in the public memory. These include the idea of a democratic renewal of the GDR, which also played a major role in the opposition movement. “In addition, what Sabrow calls ‘memory of the Wende’ is hardly a factor in the public culture of remembrance,” adds Lux. The “Wende,” which means “decisive change or turning point,” refers to a deep-seated change in everyday life.

East Berlin in 1989: People demonstrating against a possible reunification – something that is usually not prominently featured in public memory. Photo: snapshot-photography/Tobias Seeliger, Timeline Images

The view from below

The Freiburg group within the research project is exploring different notions of history in popular representations of the fall of 1989 and the following period of transformation. They are focusing on movies like “Bornholmer Straße” and “Good Bye, Lenin!,” TV shows such as “Weißensee,” graphic novels such as “Kinderland” and “Treibsand,” as well as radio broadcasts, short stories, and novels. “Popular representations are especially interesting for researching the culture of remembrance because they have a decisive influence on people’s historical awareness,” stresses Lux. Novels by authors who were teenagers in 1989 especially lend themselves well to analysis, and this generation has become more and more active in public debates about the year of the Wende since the noughties.

These novels are often autobiographical, and they capture the events of this time of change from young people’s perspective. “Through this view ‘from below,’ the authors describe how sudden, confusing, and unforeseeable these events were, which is something that often does not play a role in public memory,” says Lux, citing the novel “89/90” by Peter Richter from 2015 as an example. In his novel, Richter follows several young people in Dresden as the existing order continues to fall apart bit by bit in the year of the “Wende.” What seems set in stone one day is no longer valid the next; ideals clash, and overnight young people who had been friends suddenly find themselves on opposite sides, facing each other on the streets, armed with baseball bats.

These written works also offer insights into little analyzed areas of conflict during that time, adds Lux. Young people’s feelings of alienation from their parents is a key theme, for example, as are experiences with violence. “Novels like these demonstrate the significance of violence in everyday life in this major time change and reveal how this is still relevant today.”

Symbolic reference

The historical legacy of ’89 is even more relevant now than ever before, says Lux, who points out how the right-wing party AfD has used slogans like “Wende 2.0” or “Vollende die Wende” (Complete the Wende) in its campaigns for state elections in eastern Germany in 2019. “The successful symbolic reference to the Monday demonstrations – to concepts like ‘peaceful revolution’ and ‘Wende’ – can be traced back to deeper processes, which is why it is important to research and understand these,” says Lux.

The political significance of ’89 is also demonstrated by the use of the slogan “Wir sind das Volk” (We are the people), which came to symbolize the protests more than any other slogan 30 years ago. Today, it is being used by right-wing populists to historically justify their own agenda. Then as today, “the people” are said to be rising up against “those in charge,” against the alleged “dictatorship of opinions and attitudes.” However, this comparison does not fit by any means, according to Lux: “Not only are the conditions in today’s society completely different than in the GDR; ‘the people’ also meant something entirely different then. The fall of 1989 was about political participation, civil rights, and basic rights for all, while ‘the people,’ as the AfD understands it, marginalizes certain people and has a ‘völkisch’ connotation.”

The project’s first conference will take place at the University of Leipzig at the end of November 2019. This will be an opportunity for participants to be close to the events of 1989 not only in spirit; the conference will be held only a few hundred meters away from the St. Nicholas Church.

Judith Burggrabe