The Suffering of Others

Freiburg, Jun 05, 2019

The historian Prof. Dr. Cornelia Brink is interested in the history of photography in the 20th century and the role of gender in journalism. In her new project, which is part of the Collaborative Research Center 948 “Heroes, Heroizations, Heroisms,” the University of Freiburg scholar brings these two themes together in her research of women war photographers. Lara Wehler talked to Cornelia Brink about how the image of the hero, which continues to be dominated by men, in the field of conflict journalism has changed as more and more women have entered the field.

Elegant shoes and a gun: Gerda Taro’s photograph “Republican Militiawoman Training on the Beach outside Barcelona” from 1936 unites these two opposites. Source: International Center of Photography, New York

Prof. Dr. Brink, what characterizes the special role of women war photographers?

Cornelia Brink: Women began entering war journalism – a profession dominated by men – in the beginning of the 20th century. Women photographers, as well as their male colleagues, still have to deal with a particular idea of masculinity and hence of what defines a hero to this day. My research focuses on how women war photographers (and their male counterparts) continue to relate to this ideal since the Vietnam War – an ideal that lately appears not to be standing the test of time. I’m also interested in how women photographers develop their own types of heroines and whether any early women photographers fit this description.

How did the profession of women war photographers develop?

The first time women photographers covered a conflict was during World War I. However, they weren’t really professional photographers; they were nurses with cameras. By the middle of the 20th century, there was a relatively large number of women war photographers, most of whom worked with the US military forces. Only very few of these women became well-known, however. There were also many women war photographers after World War II, for example during the Vietnam War, who worked for major magazines. In recent times, this profession has undergone a major change. Permanent jobs at newspapers and news agencies are now rare, access to war zones is more strictly regulated, and the wars themselves have become more chaotic. Against this backdrop, the percentage of women who are war journalists has increased, although it is still relatively small. The work environment is similar to that of women soldiers – it’s a socially homogenous group that isn’t used to women working in the profession.

“The role of still images should not be underestimated today,” says Cornelia Brink. Photo: Klaus Polkowski

Why haven’t we been more aware of women in war journalism until recently?

In the last few years, women photographers have been demanding more attention and have become more publically present, also in digital media. One reason for this is that working for newspapers and agencies alone no longer guarantees them sufficient income. There have also been a number of new publications, films, and exhibitions, like “Women War Photographers” at the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, lately that focus on this theme. Today’s increased awareness of gender issues also plays a role.

What kind of heroic image exists in conflict journalism?

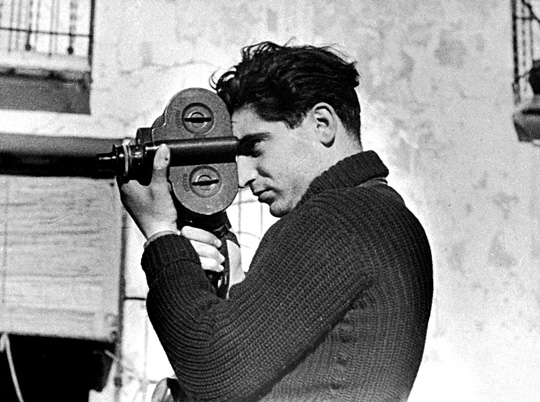

The image of the heroic war photographer is characterized by masculinity, fearlessness, courage, adventurousness, and a readiness to take risks. The photographer who goes out and covers a war to get a picture is willing to risk his life for the “truth.” Robert Capa is the prototype of this kind of heroic ideal. He died in the First Indochina War in 1954. He stands out because of his boldness and his photographer’s credo: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” But no one becomes a hero because of their skill or conduct alone; there has to be a group of people who define these qualities as heroic and admire the person as a hero. For this reason, the Robert Capa Gold Medal has been awarded since 1955 to men – and now women – war photographers, and every person who has ever received this medal confirms the type of hero defined by the medal’s eponym.

Why is heroism a matter of gender?

There are different ways to approach heroizations from a gender perspective. From the beginning, the collaborative research center has been looking for heroines. When it came to war photography, this meant making women photographers in this field visible. It soon became clear, however, that women war photographers who have been admired as heroines are few and far between. Instead, the heroic war photographer has been regarded as male: Heroism and masculinity seem to be fundamentally interconnected. This puts women on the outside, along with non-heroic men. However, things become interesting when long-held ideas about heroes no longer seem so strong. We’ve observed this in war photography for some time now, and it has consequences for the self-image of women as well as men photographers, both of whom have these old images of heroes in the back of their minds. For example, they distance themselves from these old ideas or develop new heroic models.

Bold, adventurous, and close to the action: Robert Capa is regarded as the prototype of the heroic photographer. Photo: Gerda Taro

What is the significance of gender in journalism?

It’s very enlightening for journalists to explore whether and how things that are regarded as important events in the world and are ultimately covered by the media are affected by a gender perspective. The question is whether there could be blind spots in news coverage because there are fewer female journalists than male. For example, what about the access to certain social spaces being different for women and men? Women journalists have been able to access private spaces to photograph women in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Syria. Men are usually denied access to such spaces, meaning this kind of insight is not visible in their photographs. This demonstrates how there is always a structural context behind gender relations: I can only learn what access women photographers have to a situation if I also take their male colleagues into account.

Gerda Taro’s photograph “Republican Militiawoman Training on the Beach outside Barcelona” from 1936 is considered to be especially important in this context. Why?

When we look at this photograph by Gerda Taro, who died in the Spanish Civil War in 1937 and was Robert Capa’s partner and companion, we immediately notice two things: The woman in the photograph is holding a gun, and she is wearing high heels. This doesn’t seem to add up. The gun stands for fighting, death, and hostility, while the high heels symbolize femininity, attractiveness, and dressing up. By combining these attributes, the photograph refers to something that goes beyond it, which is that general ideas about women clash with their actual role in war. The photograph also shows other male and female-connoted attributions, like the pants and the hairstyle. In the 1930s, it was exceptional for women to wear pants. Taro thus not only records a practice that was unusual at that time; the picture also becomes a kind of mirror: A woman with a camera documents another woman who is in a similarly unusual situation.

Is war photography still important in the age of moving images and the Internet?

The role of still images should not be underestimated today. This is demonstrated by how photographs are stored differently from film footage for TV. While a program that has been broadcast will often languish in an archive, photographs are shown again and again, meaning they have a different kind of continuity. However, this doesn’t mean that they are always shown in the same medium. Photographs no longer have to be printed on paper; they can be found now on Internet platforms, blogs, and online encyclopedias, where they branch out into ever new contexts. We could ask: Have photographs become even more important in the age of the Internet?