Family History in a Plastic Bag

Freiburg, Mar 12, 2019

The title “Introduction to Textual Work” is by no means a guarantee of dry and boring content. Jewish Studies’ lecturers Raban Kluger and Jan Wacker have transformed a required course into a pleasurable adventure worthy of Jane Austen. Together they have dedicated their hearts and minds to telling the story of the Ephraim family. The lecturers and their students are using more than three hundred letters, postcards, and other writings as sources. These had been handed in to the Jewish Museum in Switzerland in a plastic bag decades ago.

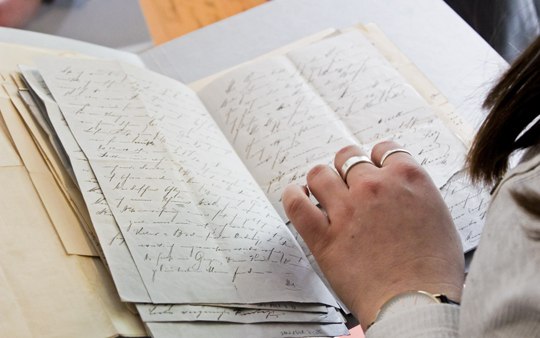

More than three hundred letters, postcards, and other texts are serving as sources for students who are searching for traces of the Ephraim family. Photo: Jan Wacker

“The idea was conceived in the summer of 2016 at a Jewish Studies’ conference in Munich,” says Jan Wacker. “A professor there told of how he deliberately focused on old synagogues in his search for manuscripts and often found writings literally stuffed into cracks,” he adds. Immediately, Wacker and Raban Kluger decided to start searching the synagogues in Alsace for texts. They intended to use manuscripts to teach students required skills such as source theory, paleography, research, and handling transcriptions as well as the Hebrew alphabet in text processing programs.

“In Freiburg, Jewish Studies is a small department with only limited financial means,” explains Kluger. “It’s too small to be able to afford expensive trips to Alsace,” he adds. With around forty students, Jewish Studies is one of the smallest departments at the University of Freiburg. But Kluger and Wacker saw no cause for despair. They remembered the Jewish Museum of Switzerland (JMS) in Basel. It is not large itself and has only modest financial, spatial, and personnel resources. This diminutive size of both turned into a win-win situation. The museum holds valuable exhibits and still unexploited documents that it would like examined. In Freiburg, there are students available who would like to sift through these treasures.

Novel characters become real

The Freiburg students started working on an unexploited bundle of three hundred items – handwritten letters, drawings, and two betrothal books from members of the Ephraim extended family. The manuscripts covered a period of around one hundred years – from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. And it was some bundle – containing as it did the stuff of a novel rather than a report.

“A man comes to the Jewish Museum in Basel. He turns out to be the adopted son of a Mr. Ephraim and hands in a plastic bag filled almost to bursting with family letters. He says he’s unable to make heads or tails of them,” reports student Carolin Mücke. She just needed to attend the basic seminar “Introduction to Textual Work” once. But Mücke found the Ephraim’s story so gripping, that she took it again the following semester and is planning to continue for the next one.

Jan Wacker (left) and Raban Kluger had the idea for the project – Carolin Mücke has worked with them for two semesters and is planning a third. Photo: Patrick Seeger

He’s lovesick, she’s correct

It’s expected that at least two more years will go by before the students have transcribed and interpreted all of the documents, estimates Kluger. Then they will be ready to tell the family story of the adoptive son with the plastic bag all the way back to the predecessors of his step-father dating back to the mid-19th century. Until then, Mücke will not be the only one working feverishly on the project. “It’s addictive, just like a television series,” she says. “We send each other photographs and bits of text and get really frustrated when the writing is completely illegible,” says Mücke.

The story has plenty of potential. Among the main items of the collection that the group processed last summer semester were the love letters between Isaak Ephraim and Lina Michaelis from 1855. “My dear, good Lienchen!” writes Isaak. “I don’t really know what I actually should say to you. My heart so longs to see you once more. You stand before my mind’s eye in every thought I have and everything I do.” Lina responds: “My friend! Of course, I honor you and hold you in high esteem. That is a given. Truly felt great regard is the basis of the friendship and I am certain therefore you will allow me to address you as a friend.”

“He’s just turned forty, but is behaving like a love-sick sixteen-year-old and occasionally gets really unpleasant. She is better behaved and doesn’t answer him enough,” says Wacker, describing the two characters. Isaak complains to Lina when she doesn’t write back quickly enough and notes when he receives and answers each letter. “He’s a real technocrat and control freak,” says Wacker. The rest of the family is just as interesting. Lina’s mother is a mother hen; her father, a hypochondriac; and the son that Lina and Isaak have together – yes, they do get together – spent money as if it grew on trees.

To be continued

The correspondence is about far more than a love story. It tells a great deal about Jewish life at a time during which legal equality of Jews raised important questions: Should they leave their communities and assimilate? In what ways could they continue living traditional life? The saga doesn’t lack celebrities, either. The Tietz family marries into the Ephraim family – including Leonhard and Oscar Tietz, who founded the department stores Hertie and Kaufhof. It’s about suicide, strange military discharges, court cases, floods, and fire damage. “It’s time consuming, and with respect to cashing in on ECTS points, it’s not really economical,” says Kluger of the project. “But when the results are exhibited at the end or presented in a publication, hopefully the students will have the feeling that the work was worth it.”

So, what do the students have to say? “It was clear to us immediately that we were working on something really unique. We are literally being allowed to touch history,” says Mücke. “At the start we were a bit overawed. Tissue paper was spread on the table, and we wore gloves. Now, we’re often there in Basel even when there aren’t seminar sessions. We get unlimited time and coffees – and want to know for sure, how things will go on for the Ephraims,” she adds. A well-known publisher has already shown interest in the work. So how do stories like this end as a rule? Guess what, with “To be continued.”