“We focus on issues that move society”

Freiburg, Feb 27, 2020

For 100 years, forestry education at the University of Freiburg has been shaped by the major issues of the respective era, whether it was the dubious glorification of the forest under the National Socialists to the environmental movement against forest dieback in the 1980s and research into the consequences of climate change. In an interview with Kristin Schwarz, Uwe Eduard Schmidt, Professor of Forest and Forest History at the University of Freiburg, embarks on a journey through time.

“Stop climate change:” In Freiburg, the “Fridays for Future” movement is demonstrating for more environmental protection. Photo: Sandra Meyndt

“Stop climate change:” In Freiburg, the “Fridays for Future” movement is demonstrating for more environmental protection. Photo: Sandra Meyndt

Mr. Schmidt, forestry education at the University of Freiburg is turning 100 years old this year. What were the early years like?

Uwe Eduard Schmidt: Strictly speaking, the University can look back on a history of more than 200 years. In 1787, Emperor Joseph II had the first professorship for forestry in Germany established in Freiburg. However, its work ended five years later when the professor was appointed to Bonn. Up to the early 20th century, university education in forestry in today's Baden-Württemberg was primarily provided in Tübingen, Hohenheim and Karlsruhe. In view of the decreasing number of students in the German Empire, a common study location was sought, and Freiburg was able to prevail over its competitor Heidelberg. Thus, in 1920, the forestry sciences returned to the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences in Freiburg with one institute and three chairs.

This development coincided with the rise of National Socialism. What consequences did the political climate have for the young institute?

The student numbers show that teaching was initially highly regarded both nationally and internationally. In 1922, out of almost 120 students, about 20 came from abroad, from Japan, the USA or Eastern Europe. This changed with the rise of National Socialism. In the early 1930s, the progressive alignment of the curriculum also made itself felt in personnel policy, for example when the chair of forest botany became vacant for ideological reasons. When the number of forestry education centers in Germany was to be reduced by half, the then dean and the mayor of Freiburg succeeded in retaining the forestry institute despite its weakened position. Between 1935 and 1937, local activities were expanded, further forestry institutes were founded and thus forestry education was secured.

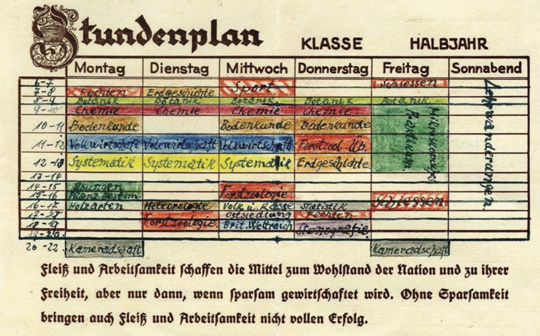

Soil science, shooting and a call for constant thrift: a timetable of a Freiburg forestry student from 1939. Source: Archive for forest and forest history, University of Freiburg

Soil science, shooting and a call for constant thrift: a timetable of a Freiburg forestry student from 1939. Source: Archive for forest and forest history, University of Freiburg

The National Socialists laid claim to the forest, glorifying it in a very dubious way and exploiting it with their policies. What did it mean for teaching?

A popular theme in Nazi ideology was equating the German forest with the German people, which was also reflected in the teaching materials. For instance, the cultivation of native tree species was linked to Nazi racial hygiene. At the same time, wood was an important raw material for the war. Researchers investigated how wood could also be used to power cars and as a textile material. As a timetable from 1939 shows, the training was very practical. In addition to educational walks, botany and soil science, shorthand was also on the curriculum to enable students to write down contents quickly. Forestry students at the front were provided with teaching materials through the military mail service. 97 percent of the students died in the War.

After the War, the forest was regarded as a safe counterpart to the destroyed city. Foresters became a dream job for men, and women valued them as loyal partners. Were the lecture halls overcrowded at that time?

They weren’t at first. Since the curriculum focused on the later work in higher administrative service, only as many students were admitted as staff was required. Those who wanted to apply had to take an aptitude test in Stuttgart and present a letter of recommendation. This meant that sons from forest dynasties had the best chances. The proportion of women was negligible. This situation changed in 1976, when a court action for equal opportunities was granted and the course of study was opened. Within a few years more than 100 students were enrolled.

Uwe Eduard Schmidt studied forestry in the 1980s and experienced a paradigm shift: students in forest green uniforms, who promoted traditional silviculture, were suddenly confronted by environmentalists. Photo: Klaus Polkowski

Uwe Eduard Schmidt studied forestry in the 1980s and experienced a paradigm shift: students in forest green uniforms, who promoted traditional silviculture, were suddenly confronted by environmentalists. Photo: Klaus Polkowski

In the 1980s, you studied forest sciences in Freiburg yourself. What was your experience during that time?

In the course of the discussion about dying forests, many people wanted to study forest sciences. This respectable aim put the previous system to the test in the best sense. Conservative students in suitably forest green uniforms, who promoted traditional silviculture, suddenly found themselves confronted by environmentalists and their idea of site-specific, near-natural silviculture. The controversial discussions ultimately led to a gradual shift in focus towards ecological issues and to a broadening of the content and methodology of forest studies. The students were to acquire basic competences in environmental issues and learn to think in a solution-oriented way. The aim was to prepare them for work beyond forest management.

Let’s take a leap into the future: After various restructurings, the Forest Sciences are now part of the Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources. What makes up the education today?

Forestry education in Freiburg has always been a reflection of current challenges. What moves society is our topic - and currently, the consequences of climate change are the most important. We are not only a young faculty, but also a young multidisciplinary college with modern approaches. In the Humboldtian sense, professors discuss current scientific opinions with students and seek solutions together. The 33 professorships and five assistant professorships cover a broad range of topics, enabling us to offer our more than 2,000 students from 51 nations a comprehensive range of German and English language courses.

Article about the anniversary of the Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources