With the help of a plenary, parliament and cabinet

Freiburg, Aug 29, 2018

Grunting and rumbling. Sometimes Prof. Dr. Karl Jakobs causes his colleagues to do the same: The experimental particle physicist from the University of Freiburg is scientific director (spokesperson) for the ATLAS project. About 3,000 scientists from 182 institutes and 38 nations work at the particle detector. Jakobs and his team make important decisions for the entire collaboration. He is the first German to work as a scientific director on an experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) particle accelerator at the CERN international research center in Geneva, Switzerland. Not every decision is cause for rejoicing. But Jakob obviously does the job well: he has just been re-elected by a large majority for a second term. Jürgen Schickinger asked the physicist how he organizes his tasks.

Since 1992 - since Day One - Karl Jakobs has been working on the ATLAS experiment. As a scientific director, he has been directing the fate of the huge project for several years.

Since 1992 - since Day One - Karl Jakobs has been working on the ATLAS experiment. As a scientific director, he has been directing the fate of the huge project for several years.

Photo: Jürgen Gocke

Mr. Jakobs, what exactly do you do as spokesperson?

Karl Jakobs: Mainly, I’m the scientific director of the ATLAS collaboration. In addition, I am responsible for external communications for ATLAS, for example for CERN management, investors from 38 countries and science journalists.

What does scientific management mean for a particle detector in concrete terms?

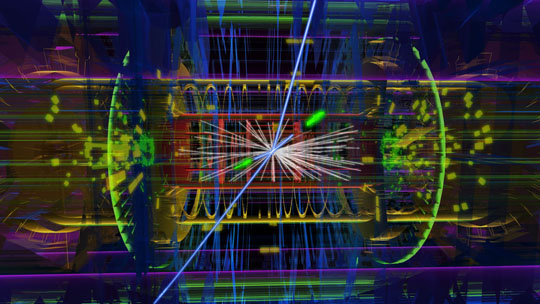

I have to set the course as to which direction the physics program of ATLAS will take. For example, the millions of particle collisions in the center of the detector provide much more data than we can capture. What fraction of the data do we pick up, which ones do we filter out immediately? Sometimes I have to make hard decisions. In addition, preparations are currently underway for ATLAS expansion to upgrade the detector for higher intensities and collision rates. From 2024 to 2026 we will install new detector components. In one area there was a concept based on established standard technology and another with a promising new technology that has great potential. However, it does not seem to me to be completely hammered out yet and we decided to use standard technology instead. Finally, I have to make sure that ATLAS is faster or at least able to keep up with the competition: the collaboration on the CMS detector at CERN pursues the same goals as we do. We are in friendly competition with one another.

The particle accelerator Large Hadron Collider is 27 kilometers long and lies 50 to 150 meters beneath the French and Swiss soil.

The particle accelerator Large Hadron Collider is 27 kilometers long and lies 50 to 150 meters beneath the French and Swiss soil.

Photo: CERN

There is rarely unity among 3,000 people. Don’t some of your decisions cause additional uproar?

Fortunately, emotional outbreaks are quite rare. Most of our meetings are very scientific. Everyone is pursuing a common goal. We try to reach consensus resolutions and solve problems quickly. But occasionally there is some moaning that goes on: recently, for example, I made myself unpopular with some workgroups that put new detector components into operation. There were significant delays because they had used too few scientists and engineers. I have asked for them now. No one wants to take over services, such as calibrating detectors. There is no glory in that. Everyone would rather analyze data and produce physics results. But services are essential for good physics analysis.

Do you address points of conflict directly or tactically?

I have a watch list of critical projects that I show at every major meeting. It’s rather exposing, but very efficient. No one wants to be on the list and if so, the group tries to be removed as quickly as possible. The worst thing you can do wrong with problematic decisions is to go to a meeting and say, “Let's do it this way and that!” That’ll make you hit a wall. To prepare informed decisions, you must discuss important issues in advance with individuals. They also bring these questions into their groups. As a scientific director they must not neglect the postdocs, the engineers and the doctoral candidates. Otherwise you will get a revolt from the base. But I do not make such decisions alone anyway.

Who is involved in the decision-making process?

We are organized much like a government. There is a “plenary,” in which all 3,000 participants can participate, and the collaboration board, a kind of “parliament,” in which all 182 participating institutes have one vote each. We have the executive board, a “cabinet” with “ministers,” each coordinating one area - such as the different detector components, data gathering or physics analysis. There is also the “head of government,” to which my management team and I as scientific director belong. The sponsors of ATLAS form a monitoring body, which I have to report twice a year. All of these groups and individuals have a say, make pre-selections, and make suggestions. In the end, the “head of government” decides.

Researchers from 38 countries want to find out what the elementary building blocks of the universe are in the ATLAS experiment at CERN, the European Laboratory for Elementary Particle Research in Geneva, Switzerland.

Researchers from 38 countries want to find out what the elementary building blocks of the universe are in the ATLAS experiment at CERN, the European Laboratory for Elementary Particle Research in Geneva, Switzerland.

Photo: CERN

How does one become scientific director for ATLAS?

All 3,000 participating physicists can suggest persons. A committee creates a selection. Then the election will take place in the collaboration board. There is no quota, such as with nationality. I believe the scientific reputation plays a role in the election, but also human qualities such as assertiveness. On the other hand, the colleagues do not want a dictator. A candidate must be open, listen to other points of view and possibly change his mind. In the end it is about classic leadership qualities.

Has the job been so much fun that you wanted to reapply?

The ATLAS collaboration wanted me to continue. Scientific directors may be re-elected once for another two-year term. Originally, I wanted to stop after a term. But now I think that two years are simply too short because it takes time to initiate and change things and to build good connections with important bodies.

After the ATLAS expansion, the experiments will start no earlier than 2026. Will you still actively participate as a scientist?

I have been working at ATLAS since 1992, which has been the bulk of my scientific life. I feel very connected to ATLAS. At present I am 58 years old. As a professor I could work until I am 68. But I do not know if I really want that. Science leaves very little time for other beautiful things, such as for the family, for traveling or reading good books. I am planning to postpone the decision for a while.